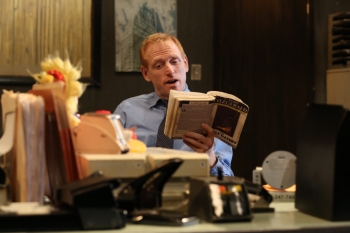

Scott Shepherd in Elevator Repair Service’s “Gatz,” which performs at Berkeley Repertory Theatre. (Photo by Steven Gunther)

- The Times of London May 10, 2012

- The New York Times December 16, 2010

- The New Yorker September 27, 2010

- New York Magazine October 6, 2010

- The New York Times October 6, 2010

- The New York Times February 5, 2010

- The Boston Globe May 15, 2009

- The Sydney Morning Herald December 28, 2009

- The Sydney Morning Herald May 19, 2009

- The Chicago Tribune November 17, 2008

- Time Out Chicago November 13-19, 2008

- Chicago Sun-Times November 15, 2008

- The Irish Times October 4, 2008

- The Independent October 3, 2008

- Irish Times September 29, 2008

- ArtForum: Best of 2007 December 1, 2007

- The New York Times Magazine December 9, 2007

- The New York Times September 16, 2007

- The Village Voice September 12-18, 2007

- The Bulletin September 4, 2007

- Publico July 4, 2007

- Die Presse June 17, 2007

- Klassekampen December 12, 2006

- Variety October 1, 2006

- Neue Zürcher Zeitung August 28, 2006

- Landboote August 28, 2006

- Tages-Anzeiger August 28, 2006

- The New York Times July 16, 2006

- Het Parool June 16,2006

- 8Weekly June 16, 2006

- Trouw June 16, 2006

- Walker Art Center interview June 8, 2006

- NRC Handelsblad June 2, 2006

- De Volkskrant May 29, 2006

- Le Soir May 24, 2006

- Yale Alumni Magazine November/December 2005

Review: ‘The Great Gatsby’ shines anew in this 8-hour (plus) staging

Our greatest novels needn’t lie buried under the sediment of youth syllabi, freighted with the baggage of their own greatness. They needn’t feel faraway and foregone, like historical artifacts.

No, says “Gatz,” they can slip into the most mundane moments of your life right now — maybe like that moment when you coast into your office and plop down in front of your ancient computer, only to find it won’t turn on, no matter which buttons you press.

That’s how Elevator Repair Service’s production, an all-day reading of “The Great Gatsby” in its entirety, begins. If you can’t get any work done, why not take out a well-worn copy of F. Scott Fitzgerald’s novel and start reading aloud?

The company, brought from New York by Berkeley Rep, where the show opened Thursday, Feb. 13, treats its audience with rare care and respect. It knows its staggering ambition asks a lot of us: almost nine hours of our day (with breaks, including a two-hour span for dinner). But it also trusts that we can accept and adjust to the realities of an unconventional dramatic universe, one where an idle office worker (Scott Shepherd) starts reading aloud and his office mates barely register the change. He gets only a moment of eye contact, a slight brightening in facial expression, the way you tacitly acknowledge someone you pass a thousand times a day in the hallway.

But as the 12 other ensemble members gradually populate the drab office around the reader, starting their morning, you might begin to notice strange concurrences, like how someone makes an entrance right at a moment of change in the reading, or the way another actor seems to take on, just for an instant, the aura of a character being described.

Then it happens: Actor Susie Sokol joins in with Shepherd to read a line aloud. For Shepherd isn’t just a reader but Gatsby narrator Nick Carraway himself, and his office mates become the whole crew: ethereal Daisy (Annie McNamara), ursine Tom (Robert M. Johanson), affected Gatsby (Jim Fletcher), aloof Jordan Baker (Sokol), overflowing Myrtle (Laurena Allan) and pathetic George Wilson (Frank Boyd).

A big reason the show’s mighty gamble pays off is the technical prowess of Shepherd as Carraway, literature’s amiable, unknowable receptacle, that cipher who’s always ready to absorb what the shimmery, fizzy Jazz Age has to offer him, and reflect it back with commentary that’s sometimes dry, sometimes wistful, but all without imprinting any of his own desires on it. He’s a mere conduit for Gatsby’s runaway ideals, self-mythologizing and hopeless romance; he’s happy to report on Roaring ’20s excess without being touched by it.

Shepherd’s weathered, world-weary voice would be right at home in a Western, but it has a liquid’s power to morph into the sloppy opulence of a New York accent or the breathy restraint of femininity. He lands on syllables or leaves them hanging or drives them forward, dropping a pitch here, raising it there, with the refined eye of a wood carver, but without any fuss. Fitzgerald’s language is fruit ripe to bursting, and Shepherd plucks each word as if he’s cupping his hand underneath it, knowing exactly when it’ll fall without having to exert force.

But each cast member excels. McNamara’s Daisy, Gatsby’s beloved, is already shattered before the story breaks her, a million pieces catching the light that someone might see her and put her back together again. Johanson’s Tom, Daisy’s husband, bowls through a room like everyone else is a pin to be knocked over. Fletcher’s Gatsby keeps his face as severe and opaque as stone, but with a pool of sadness right underneath the surface.

Still another star of the show is the sound, not least because designer Ben Jalosa Williams operates the sound board onstage, playing minor roles, occasionally leaping up for a brief speaking part between two flips of the switch, headphones still on his head. His frogs and crickets make Long Island twinkle with magic; a distant, distant orchestra makes life seem yearned for even as it’s being lived. His rendering of a car crash conjures the fleshy thud of human body on metal — you can almost hear, in just an instant, organs and liquids roiling around inside as engines roar and roar and then abruptly cut, giving you space to absorb the horror.

Director John Collins can make a party scene as dangerous and explosive as fireworks. His ensemble so swerve and burst in their movements that you half-expect the set to fissure and a geyser to shoot through. But he can also invest deeply in long, meditative moments of quiet, the sort that an audience might not have patience for in a show of standard length.

That’s one of the rewards of marathon theater, for all its demands on your time. You feel yourself opening up as a spectator. You become more willing to take risks, to follow where a show leads. You already know you’ve committed your day, so you can lean back and lean in at the same time.

In 2020, it might discomfit to think about how a novel about the 1% of the 1% is so foundational to our country’s literature. But especially if you haven’t encountered “Gatsby” in years, you might be pleasantly surprised or reminded by how the book keeps reaching beyond, zooming out from the narrow, skewed perspective of its privileged central characters. Fitzgerald’s words make them immediate, earthy, putrid in their humanity, combustible balls bouncing around in prisons of their own making. Onstage, with no Art Deco glitz, only office gloom, that humanity shines anew. It’s the joy of discovery and rediscovery all at once.