- San Francisco Chronicle February 14, 2020

- The Times of London May 10, 2012

- The New York Times December 16, 2010

- The New Yorker September 27, 2010

- New York Magazine October 6, 2010

- The New York Times October 6, 2010

- The New York Times February 5, 2010

- The Boston Globe May 15, 2009

- The Sydney Morning Herald December 28, 2009

- The Sydney Morning Herald May 19, 2009

- The Chicago Tribune November 17, 2008

- Time Out Chicago November 13-19, 2008

- Chicago Sun-Times November 15, 2008

- The Irish Times October 4, 2008

- The Independent October 3, 2008

- Irish Times September 29, 2008

- ArtForum: Best of 2007 December 1, 2007

- The New York Times Magazine December 9, 2007

- The New York Times September 16, 2007

- The Bulletin September 4, 2007

- Publico July 4, 2007

- Die Presse June 17, 2007

- Klassekampen December 12, 2006

- Variety October 1, 2006

- Neue Zürcher Zeitung August 28, 2006

- Landboote August 28, 2006

- Tages-Anzeiger August 28, 2006

- The New York Times July 16, 2006

- Het Parool June 16,2006

- 8Weekly June 16, 2006

- Trouw June 16, 2006

- Walker Art Center interview June 8, 2006

- NRC Handelsblad June 2, 2006

- De Volkskrant May 29, 2006

- Le Soir May 24, 2006

- Yale Alumni Magazine November/December 2005

Avant-Garde, PA

by Alexis Soloski

In his autobiography, Benjamin Franklin, Philadelphia’s favorite son, lists the 13 virtues that will lead to “moral perfection”—moderation, temperance, and cleanliness among them. Immoderate, intemperate, and frequently dirty, the Philadelphia Live Arts Festival wouldn’t fare well in Franklin’s estimation. Now in its 11th year, this celebration of innovative arts might occasion moral turpitude. But a sampling of its theater offerings suggests it might also occasion a very pleasant weekend.

New York audiences could construe Live Arts as a larger Under the Radar or a low-rent Lincoln Center Fest. Running through September 15 in concert with the Philly Fringe, Live Arts treats Philadelphia audiences to some of the most playful and daring work available. Curator Nick Stuccio’s tastes seem to run toward both the somber and the ludic. He’s booked everything from Coco Fusco’s very serious piece about women in the military to Young Jean Lee’s uproarious, irreverent Songs of the Dragons Flying to Heaven. Each day’s performances conclude with a late-night cabaret—its insalubrious location off Spring Garden Street (shattered glass, broken sidewalks, heavy on the vagrants) doesn’t deter a couple hundred performers, organizers, and audience members from gathering for indifferent nightclub acts, cheap booze, and lively conversation.

Many of the festival’s offerings—Lee’s play, the Wooster Group’s The Emperor Jones, the Nature Theater of Oklahoma’s No Dice—have been or will be seen in New York. Elevator Repair Service’s Gatz, a wondrous staging of F. Scott Fitzgerald’s The Great Gatsby, has not and will not— at least any time soon. For years, ERS has lobbied the Fitzgerald estate for permission to perform the piece. The estate, which apparently still dreams of another Broadway adaptation, has barred the group from presenting the production in New York. Even a no-charge workshop at the Performing Garage in 2005 received a cease-and-desist order. Consequently, many New Yorkers peppered the Philly audience at one of the show’s seven-and-a-half-hour performances. Those hours include two brief intermissions, a longer dinner break, and absolutely every word of Fitzgerald’s novel—every aside, every descriptive passage, every “he said” and “she laughed.”

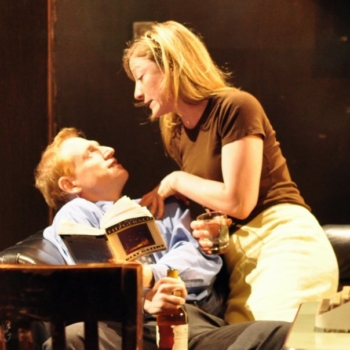

In a down-at-the-heels office, an idle employee, Scott Shepherd, picks up a paperback copy of The Great Gatsby and begins to read aloud to himself. At first his coworkers ignore him, but they gradually begin to take an interest in the text, speaking dialogue and contributing gestures. The scene doesn’t alter, yet office surroundings somehow dim. By a quiet sort of magic—and some clever sound design—the stacks of files and the business-casual outfits come to represent the glitter and pomp of Gatsby’s West Egg mansion and its begowned guests.

Cleverly, director John Collins never allows this illusion to triumph. The Great Gatsby is a novel of ambition, of desire. Like Fitzgerald, Collins doesn’t permit those ambitions to be achieved or those desires fulfilled. In a poignant passage describing Gatsby and Daisy out for an evening stroll, Fitzgerald writes, “He knew that when he kissed this girl and forever wed his unutterable visions to her perishable breath, his mind would never romp again like the mind of god. . . . Then he kissed her.” But Gatz doesn’t make Gatsby’s mistake—it resists and delays that consummation, refusing to allow the stage action to ever entirely replace the novel Shepherd holds. Just when we might become carried away, might give ourselves over to the figures before us, a secretary enters with a stack of documents or a telephone rings. With a jolt we find ourselves transported back to the office, suddenly conscious that the tinsel and shimmer exist in our mind alone, that only a dreary workplace greets our eyes. Instead of giving us the comfort of a mimetic fantasy, ERS implicates us in a singularly imaginative act, not dissimilar to the one young Jimmy Gatz attempted when he remolded himself Jay Gatsby.

The novel’s Gatsby could never entirely inhabit his new role. Similarly, the actors merely sketch the characters or, as in the case of Susie Sokol’s Jordan Baker, play them defiantly against type. No actor quite looks his part. When Shepherd reads how the breeze tousled Gatsby’s hair, Shepherd and Jim Fletcher (the mostly bald man performing Gatsby) exchange an apologetic smile. We are always made aware of the gap between what we actually see and what we ought to, Gatz and Gatsby at once. It’s an extraordinary double vision, one we can’t help trying and failing to unite. The novel’s end describes a similar effort, how we all yearn for “the orgastic future that year by year recedes before us. It eluded us then, but that’s no matter—tomorrow we will run faster, stretch out our arms farther. . . . And one fine morning—” In the meantime, ERS presents a very fine afternoon and evening.