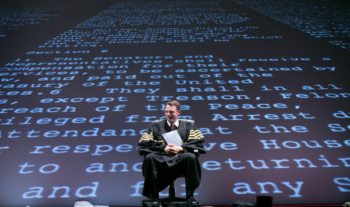

Ben Williams. Photo by Sara Krulwich/The New York Times

- Washingtonian April 4, 2014

- Chicago Sun Times March 12, 2014

- Chicago Tribune March 16, 2014

- Slate October 23, 2013

- Metro US October 21, 2013

- The American Conservative October 18, 2013

- Wall Street Journal October 7, 2013

- Gothamist October 2, 2013

- New York Magazine September 26, 2013

- Broadway World September 24, 2013

- The New York Observer September 24, 2013

- The Village Voice September 25, 2013

- Entertainment Weekly September 24, 2013

- Theater Mania September 24, 2013

- Curtain Up September 25, 2013

- The Village Voice September 4, 2013

- The Paris Review May 31, 2012

Full-Frontal Justice, a Matter of Redress

by Ben Brantley

A cool, obsessive genius animates the ever more fevered proceedings of “Arguendo,” the Elevator Repair Service’s foray into the hallowed mazes of American jurisprudence. Come to think of it, jurisprudence doesn’t describe what’s happening here. “Jurisfolly” would be closer. In this anatomy of a 1991 legal case, now being re-enacted at the Public Theater, order in the court — the Supreme Court, no less — is not an option.

Or not in any way that a judge would deem desirable. Under the direction of John Collins, “Arguendo” holds on to the chaos-out-of-order formula that characterized the Elevator Repair Service’s improbably successful verbatim adaptations of “The Sun Also Rises,” “The Sound and the Fury” and “The Great Gatsby,” which was called “Gatz” and was a megahit at the Public a few years ago.

In such productions, Mr. Collins and company elicited the molten, heaving quality in impeccable prose, the hot souls within cold print. What we experienced with those shows, especially “Gatz,” was what we undergo when we are so in thrall to a great novel that its rhythms become our own. Applying the same approach to legalese and court transcripts doesn’t sound like a whole lot of fun, even if the res is as racy as a strip club’s right to free expression.

It’s true that the extempore utterances of Justices Scalia, Souter, Kennedy, et al. are not quite on a level with the sentences of Fitzgerald and Faulkner. But “Arguendo,” which opened on Tuesday night and runs through Oct. 13, is so wittily inventive that it makes you think that the Elevator Repair Service might as well have a go at the Pittsburgh phone directory next. If anyone could find the poetry therein, it’s this troupe.

The poetry that is discovered within Barnes v. Glen Theater — in which a group of exotic dancers in South Bend, Ind., challenged a state ban on public nudity — often sounds like stately nonsense verse, the kind that Lewis Carroll invented to appeal to children’s sense of the ridiculousness of grown-ups. The words emerge from the mouths of five performers, and I had to go back and consult my program to make sure there were only five, because they seem like at least four times that number.

They are Maggie Hoffman, an intrepid Mike Iveson, Vin Knight, Susie Sokol (who does a marvelous Ruth Bader Ginsburg) and the most fine-tuned of the lot, Ben Williams, who has a devastating gift for understated exaggeration. They play members of the Supreme Court, the attorneys addressing them, reporters and one exotic dancer.

Here is a randomly chosen, thoroughly typical example of the dialogue from this play: “And for that reason this is the type of general prohibition that this Court … such as the one in Employment Division v. Smith … can be applied consistent with the First Amendment notwithstanding a claim that the conduct at issue is protected.” Yeah, I know, wake me when it’s over. Except, and this is a big except, this very dry language is being used to consider whether legally mandating strippers to wear pasties and g-strings (instead of nothing at all) is a violation of their First Amendment right to free speech. This makes for an automatic collision of form and content. And less subtly skewed and resourceful minds than those at work in “Arguendo” (which means “for the sake of argument”) might simply mine the obvious comic appeal of grandly dignified judges being turned into dirty old voyeurs.

The production doesn’t follow that route. It does have a fine time pursuing the equally obvious path of the accelerating absurdity of the rhetoric employed here, and the maddening density of legal references. Pages of text loop, swirl and zoom in and out of focus on the screen in ways that match the delirious circularity of what you’re hearing. (The media software is designed by the Office for Creative Research; Ben Rubin is the projection designer, and David Zinn did the set.)

The justices propel themselves about the stage on black swivel chairs in precise, ever more eccentric ways that eventually suggest a kind of orgiastic ballet. (Katherine Profeta is credited as the “movement dramaturge.”) And the play’s frenzied climax — of which I will say nothing except that it does involve, as you will be warned, full-frontal nudity — might have come from a Joe Orton farce.

But there’s surprising depth within these absurdist high jinks, though you may not quite realize it until near the production’s end. While presenting the esoteric legal arguments for what constitutes creative expression, “Arguendo” is giving us a purely theatrical and more far-reaching version of that same debate.

The vocal and physical tics of the Supreme Court justices, in particular, are stylized and magnified in ways that force us to look upon what they do and say as a kind of expressive dance in itself. The subliminal question put forth is whether every move we make is an artistic expression.

Or at least that’s what I inferred when I thought about the show after. One of the privileges of being a critic is that you are required to keep thinking about what you’ve seen. “Arguendo” is one of those shows that, while occasionally tedious in the viewing (even at 80 minutes), keeps growing richer and more insightful in the remembrance.

Watching “Arguendo” is rather like spending time with a friend who is given to fanatical fixations on subjects you think you don’t really care about. At first you’re amused by the improbably intense interest of said friend, who can’t stop talking on the subject. Then amusement turns to annoyance, then resigned boredom. But at some point the pure energy and relentless detail of her passion infects you, and you start to view the world through her eyes.

What you see is a teeming, fertile landscape you never knew existed. So, yes, count me in if the Elevator Repair Service decides to take on that phone book as its next project.

View the original article here.